Indian Textile Industry is experiencing a period of stress. A dark cloud of decline is slowly enveloping the textile value chain right from spinning segment onwards. H1’23 experienced decline in demand in key international markets along with a slowing domestic market, topped with increasing competition from other Asian manufacturer suppliers. Receding demand in the US and EU markets have pushed the spinning mills in Tamil Nadu, India to halt production & sale of yarn. Tamil Nadu is home to more than 50% of the spinning mills in India. TASMA (Tamil Nadu Spinning Mills Association) is demanding to negotiate a restructuring of existing credit lines from the scheduled commercial banks. They are seeking an expanded moratorium along with a longer tenor on their existing portfolio of borrowings. According to TASMA, a large number of spinning mills are currently on the cusp of being declared NPA (Non Performing Asset). But why did a situation like this shape up in the first place?

Decline in demand from key importing nations is not the only reason for this situation. This precarious situation of the industry is attributed to several reasons:

- Slowed demand in international and national markets

- Increase in MSP (minimum support price) and imposing higher import duty on cotton

- Competition from countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia etc.

- Increasing borrowing cost

These reasons should be studied in three separate buckets:

- Input costs: Over the previous two years, India has implemented two simultaneous steps which led to an increase in input cost. Government increased the MSP for cotton by up to 10% to support domestic cotton farmers. Further, an import duty was imposed on import of cotton. The government implemented these steps with an intent to support the farmers but these steps may have been implemented without a comprehensive impact analysis on overall competitiveness of the textile value chain. The input cost further worsened with the added increase in borrowing cost along with the service cost for additional borrowings that the sector made to tide through the COVID overheads.

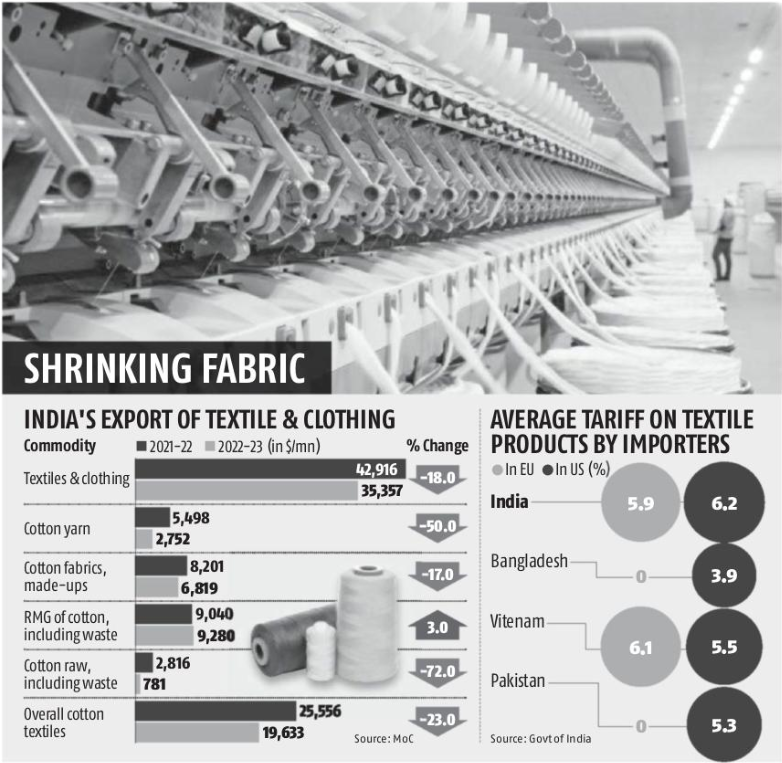

- Competition: The price difference between India and players from Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia range from 15% – 20%. Vietnam for instance has an FTA (Free Trade Agreement) with EU which gives it a custom duty advantage of 8-12 percent. Bangladesh, Myanmar and Cambodia being least developed countries gain from nil customs duty. Pakistan and Srikanka also attract the benefit of nil duty on account of Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus( GSP+) category; a benefit that India lost during Trump administration in 2019. On a net basis in the US and the EU, Indian textile attract a higher 6% duty compared to its competition.

- Demand: While FY’22 did not see a downshift in demand, FY’23 is experiencing demand slide across the EU markets marginally and the US markets significantly. A lot of this can be attributed to the food led core inflation where consumers have been forced to balance their domestic budgets on account of increase in the cost of their food baskets.

India of late has been moving to develop several manufacturing sectors through incentives structured around Performance Linked Incentives (PLI). In this quest, it should not lose on to existing strength which are in place and has matured through years of efforts. Alternatively, textile can also be also looked as a low value add, less technology intensive, people intensive business and hence a desire to move in to high value add technology intensive businesses as a way forward for the Country. But the demographic structure of India which it carries as a huge population along with a high proportion of young employable segment; hence a sector like textile cannot be ignored which creates a huge employment base.